The students in my Freshman Honors class have certain expectations for how a math class works – a teacher lectures, there’s lots of drill practice, and then a test. Breaking this mold, and causing them to think of themselves as reflective learners, is one of my many missions. So this past week, when confronted with factoring, I simply refused to lecture.

My 9th graders have seen factoring before, but it was back in 7th grade, and it was only a surface treatment. So after a brief opener where we discussed what a “factor” means (both numerically and algebraically), I dropped the bomb –

- I’ve posted your learning targets online

- I’ve posted videos, resources and practice problems if you need them

- I’ve set up online practice if you need it

- You have a timed quiz on Friday (we started on Tuesday)

And….scene!

Panic….apprehension….incredulous looks….

So, you’re not going to teach us?

Nope. Now get to work.

Here are some details of what I posted:

LEARNING TARGETS

- F1: I can identify and factor expressions which involve greatest common factors.

- F2: I can efficiently factor trinomials of the form ax2+bx+c, where a = 1.

- F3: I can factor trinomials of the form ax2+bx+c, where a does not equal 1 (or zero).

- F4: I can identify and factor perfect square trinomials.

- F5: I can identify and factor “difference of squares” expressions.

- F6: I can factor expressions which may represent a combination of F1 to F5.

- F7: I can factor expressions “by parts” (or “by grouping”) when necessary.

- F8: I can factor expressions which are the sum (or difference) of two cubes.

RESOURCES

Each learning target featured a video – some from Khan Academy, and some from other sources I searched for – but I attempted to provide a variety of methods. Some featured grouping as a primary means, others demonstrated the box method or the diamond. This was the most important aspect of this learning experience: I wanted students to experience a variety of approaches, evaluate them, and make a personal decision about what worked best for them. The students did not disappoint.

I also posted other online resources, such as worked examples and flowcharts. One of my favorite resources – Finding Factors from nrich, was also included. Finally, I created an assignment on DeltaMath for each learning target, and a final jumbled assignment. The end of each day featured an exit ticket quiz and recap, to assess progress and provide “next steps” during the week.

SO WHAT HAPPENED?

Some students latched onto factoring by grouping for every quadratic, and explained their reasoning to their peers. Many of these same students later in the week found more confidence in their number sense and chose to group only for “tricky” problems. One student was particularly insistent that the box method was the best was to go for all problems. Others found the diamond method helpful – which led to deep conversations about number sense and how to make searches more efficient. And in one fascinating conversation, a student discovered a “trick” he had found online. The group debated the merits of the method, tried some practice…but as nobody in the group could figure out why the method worked, they quickly dismissed it. Good boys!!!

In the end, the quiz scores were great. But beyond the scores, I feel confident that the students have made choices about their learning, assessed and revised their thinking, and can move forward using their new tools.

WHAT DID THE STUDENTS THINK?

Today I asked students to reflect upon their learning experience, and provide me feedback.

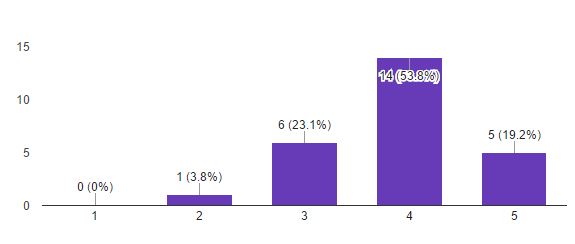

What was your overall feeling about last week’s learning method? (1 = “Please never do that again”, 5 = “I loved it – do it more”.)

Describe something you LIKED about last week’s classes, and why you liked it.

- I liked being able to choose what i wanted to do. I could focus on my weaknesses and do less problems on what i was good at. I also appreciated the practice problems.

- I liked that if you knew a topic you could move on and didn’t have to wait for someone else or the next day of class.

- I liked that I could learn and do problems at my own speed.

Describe something you DIDN’T LIKE about last week’s classes, and why you didn’t like it.

- I did not like that you did not explain how to factor

- I didn’t have as much instruction from the master of factoring. {note – I suppose this is me?}

- the teacher wasn’t involved

This last comment intrigues me…and I’m not sure if I should be bothered by it…I don’t think I should be. In many respects, I feel I worked harder during the classes, as students were all over the place. But I also realize students don’t see all of this going on around them. I’ve become intrigued by how I can be less of a teacher and more of a facilitator in my classes, and this was a solid step forward I feel.

Now, off to plan to not lecture tomorrow….

In my

In my  nts then used their technology-based procedure to actually draw a random sample of 10 squares, marking off the squares. But counting the actual stars is not reasonable, given their quantity – so it’s Beth Chance to the rescue! Make sure you click the “stars” population to get started. Beth has provided the number of stars in each square, and information regarding density, row and column to think about later.

nts then used their technology-based procedure to actually draw a random sample of 10 squares, marking off the squares. But counting the actual stars is not reasonable, given their quantity – so it’s Beth Chance to the rescue! Make sure you click the “stars” population to get started. Beth has provided the number of stars in each square, and information regarding density, row and column to think about later.