Expected Value – such a great time to talk about games, probability, and decision making! Today’s lesson started with a Monopoly board in the center of the room. I had populated the “high end” and brown properties with houses and hotels. Here’s the challenge:

Expected Value – such a great time to talk about games, probability, and decision making! Today’s lesson started with a Monopoly board in the center of the room. I had populated the “high end” and brown properties with houses and hotels. Here’s the challenge:

When I play Monopoly, my strategy is often to buy and build on the cheaper properties. This leaves me somewhat scared when I head towards the “high rent” area if my opponents built there. It is now my turn to roll the dice. Taking a look at the board, and assuming that my opponents own all of the houses and hotels you see, what would be the WORST square for me to be on right now? What would be the BEST square?

For this question, we assumed that my current location is between the B&O and the Short Line Railroads. The conversation quickly went into overdrive – students debating their ideas, talking about strategy, and also helping explain the scenario to students not as familiar with the game (thankfully, it seems our tech-savvy kids still play Monopoly!). Many students noted not only the awfulness of landing on Park Place or Boardwalk, but also how some common sums with two dice would make landing on undesirable squares more likely.

ANALYZING THE GAME

After our initial debates, I led students through an analysis, which eventually led to the introduction of Expected Value as a useful statistic to summarize the game. Students could start on any square they wanted, and I challenged groups to each select a different square to analyze. Here are the steps we followed.

First, we listed all the possible sums with 2 dice, from 2 to 12.

Next, we listed the Monopoly Board space each die roll would causes us to land on (abbreviated to make it easier).

Next, we looked at the dollar “value” of each space. For example, landing on Boardwalk with a hotel has a value of -$2,000. For convenience, we made squares like Chance worth $0. Luxury Tax is worth -$100. We agreed to make Railroads worth -$100 as an average. Landing on Go was our only profitable outcome, worth +$200. Finally, “Go to Jail” was deemed worth $0, mostly out of convenience.

Finally, we listed the probability of each roll from 2 to 12.

Now for the tricky computations. I moved away from Monopoly for a moment to introduce a basic example to support the computation of expected value.

I roll a die – if it comes out “6” you get 10 Jolly Ranchers, otherwise, you get 1. What’s the average number of candies I give out each roll?

This was sufficient to develop need for multiplying in our Monopoly table – multiply each value by its probability, find the sum of these and we’ll have something called Expected Value. For each initial square, students verified their solutions and we shared them on a class Monopoly board.

The meaning of these numbers then held importance in the context of the problem – “I may land on Park Place, I may roll and hit nothing, but on average I will lose $588 from this position”.

HOMEWORK CHALLENGE: since this went so well as a lesson today, I held to the theme in providing an additional assignment:

Imagine my opponent starts on Free Parking. I own all 3 yellow properties, but can only afford to purchase 8 houses total. How should I arrange the houses in order to inflict the highest potential damage to my opponent?

I’m looking forward to interesting work when we get back to school!

Note: I discussed my ideas about this topic in a previous post. Enjoy!

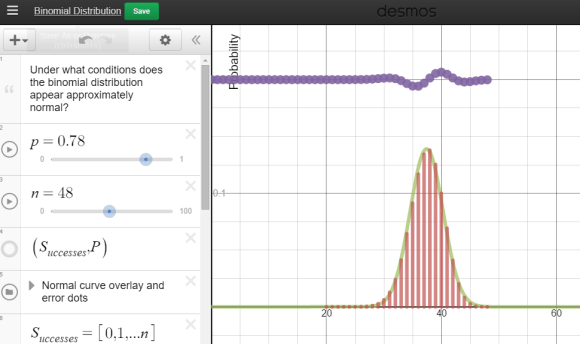

Each group was equipped with a netbook, and some students chose to use their phones. A Desmos

Each group was equipped with a netbook, and some students chose to use their phones. A Desmos