At my high school, I host “math lab” on alternate days. The lab is an open room where students can obtain math help during their lunch or free period. I like this assignment because I get to see a lot of different kids during the week, gain some insight into the approaches of my colleagues, and get my hands dirty in many math courses.

Last week one of my “regulars”, who often leaves class early for sports, came to the lab for Algebra 2 help. He missed out on a adding/subtracting rational expressions lesson, but had the notesheets handy. We wrote the first problem on the board:

Nothing too fancy. But in math lab, I don’t know the students as well as my own, so I need to do a quick check for some background before diving into new material. A spot check for understanding of fraction operations was in order:

The student approached the board confidently and “added” the fractions:

…sigh…. sometimes there isn’t enough coffee in the world. But all is not lost, and after a stare-down, the student recognized he had acted too quickly, and completed the problem correctly. This led to another problem. This time, I asked the student to just tell what me what the common denominator would be:

Without hesitation, the student knew the correct denominator to be 24. But why is it 24? The student could not defend his answer, but was absolutely sure 24 was the LCD. On the one hand, I am happy that the student has achived enough fluency with his number sense to confidently find the denominator. But, on the other hand, has lack of a process is going to hurt us now when we try to apply LCD’s to algebraic expressions.

TRY THIS WITH YOUR STUDENTS

When I start my lesson on adding rational expressions, I hand out index cards to every student. I give students 2 minutes to repond to the following prompt:

How do you find a least common denominator? Provide directions for finding an LCD to somebody who does not know how to find one.

I collect all of the cards, shuffle them, and choose a few randomly to share under the document camera. We will discuss the validity of the explanations, and use parts of the explanations to come up with a class-wide definition of an LCD. Here is what you can expect to get back on the cards:

- Some students will recognize that factors play a role, but won’t recognize that the powers of the factors are imporant.

- Many students will attempt to use an example as their definition. This allows for a discussion of a mathematical definition. Is one example helpful in establishing a rule? How about 2 examples? How are examples helpful, if the reader does not know how to find an LCD?

- Some students will provide a hybrid of the last two bullets.

- If a student does provide a suitable definition, it’s time for you to play dumb. Let the class assess the language and verify that the definition is, or is not, suitable. In one class, I “planted” a working definition in with the student cards to see if they could identify a working definition.

The Least Common Denominator of two or more fractions is the product of the factors of all denominators, raised to the highest power with which they appear in any denominator.

HOW DO EARLIER MATH EXPERIENCES PROVIDE A SUITABLE BACKGROUND FOR RATIONAL EXPRESSIONS IN ALGEBRA?

I am curious how math teachers approach Least Common Denominators in earlier grades, and how these approaches translate to algebra success. Here’s how a few online math sites approach LCD’s.

First up, mathisfun (search for “Least Common Denominator):

This is the approach I suspect many teachers take to help students find LCD’s. It works for manageable denominators, but becomes cumbersome when we have 3 or more denominators to consider, and certainly is not helpful in our algebra world. Also, if you get too confused, you can use the “Least Common Multiple Tool” this website provides. I suppose it’s not an inappropriate method, but a more algebra-friendly process should eventually develop.

Next up, Everyday Mathematics at Home website:

The good news – we have a formal definition!

The bad news – you have to know what an LCM is to use it.

This is a more formal version of the Mathisfun example. We could adapt it for use in algebra, but again, a definition of LCM is required here.

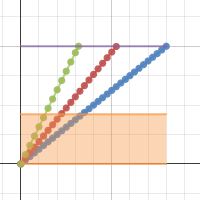

Khan Academy starts by using lists of multiples and provides and example with a trio of numbers for which we want the LCM:

The factor trees and the color verification that all 6, 15, and 10 are all factors of 30 is nice, but this example conveniently leaves out any scenario where a number is a factor multiple times, and this is the only example given.

Finally, let’s check out how PurpleMath tackles LCM’s, with a non-intuitive example:

Now we are getting someplace. Not only does this method stress the importance of factors, it shows the importance of include all powers of those factors. And I could transfer this method easily to algebra class!

Have any insihgts into teaching LCD’s, either for a fractions unit, or in algebra? Would enjoy hearing ideas, feedback and reflections!